Time, Space, Money

It is January in Michigan and I am looking out my studio window at the white that has covered the field and trees. Winter is a focused time in my studio. It has given me pause to think about how I came to be an artist.

Over time I have learned there are three essential things that any artist needs to succeed. Time- to be able to make work, a space -to be able to make work, and money- to survive and build an art practice.

I didn’t always realize these were crucial to surviving as an artist. In 1982, eager and fresh out of graduate school, I moved to Frankfort, a small northern town on Lake Michigan, to work in a small wooden boat shop. I planned to work full-time in the boat shop to pay my bills and learn new woodworking skills while working to be an artist in the evenings and weekends.

After a couple of summers, the small boat shop folded. I went to work at a local gas station/store, and then a local lumber yard. With each new job, I felt further away from the art world I wanted to be in. I didn’t have a dedicated studio space. Had anything been available in my small town, I certainly couldn’t afford it. I made do with an extra bedroom in my rental house, but working in a bedroom that says bedroom every time I entered began to erode my drive to make art. It wasn’t what I imagined or needed a studio to be. Weekday nights working in the dimly lit bedroom studio turned into weekends. I was struggling to stay connected to art. Struggling to financially make ends meet. Struggling to still be able to call myself an artist.

Desperately wanting a more committed art practice in 1989 I applied for a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. I don’t remember how I first became aware of the program. More than likely it was a listing of grant and exhibition opportunities in a newsletter from a local artist association in Traverse City. To complete the application I needed to have 20 slides of my current work. I didn’t have my own photographic equipment so I had to hire a professional photographer. The complete application was then mailed in to be reviewed by a national group of professional working artists and gallerists. After several months I received a very governmental-looking letter in the mail. I nervously opened it to read that I had been awarded a grant for $5000.

My mind was reeling with new possibilities. $5000 was more money than my bank account had ever seen. The grant gave me the confidence to search for and commit to a dedicated studio space, which I did find. It was small, only 400 square feet, with a tiny basement window, but it was my first real studio.

Someone suggested I do an up-and-coming art fair in a wealthy suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. I didn’t have gallery representation at the time, and art fairs were not that common. I knew very little about what they entailed but I took the risk. I took some of the grant money to buy an outdoor pop-up tent, build a plywood display, and I bought a 1982 Dodge pickup for $1500. I loaded the truck with everything and drove 8 hours to the two-day event. I remember going back to my Motel 6 room, counting the money, and jumping up and down on the bed to the sum of $2000, throwing the bills into the air. Later that summer I got into the Ann Arbor Art Fair, the biggest art fair in my home state. I couldn’t believe it when I sold almost everything I brought with me. With the same body of work I applied to Objects Gallery, an established Chicago gallery. Ann Nathan, the gallery owner, agreed to represent me and would prove to be a driving force in my art career. I saw that I might be able to be a full-time artist and I took another risk. I quit my job at the lumber yard.

Had I not received the financial assistance from the NEA grant, along with its peer recognition, I might not have continued making art. I was just getting by and had felt myself losing steam. The grant was a symbolic connection to a body of working artists across the country, and it gave me the seed money to be able to build my art practice.

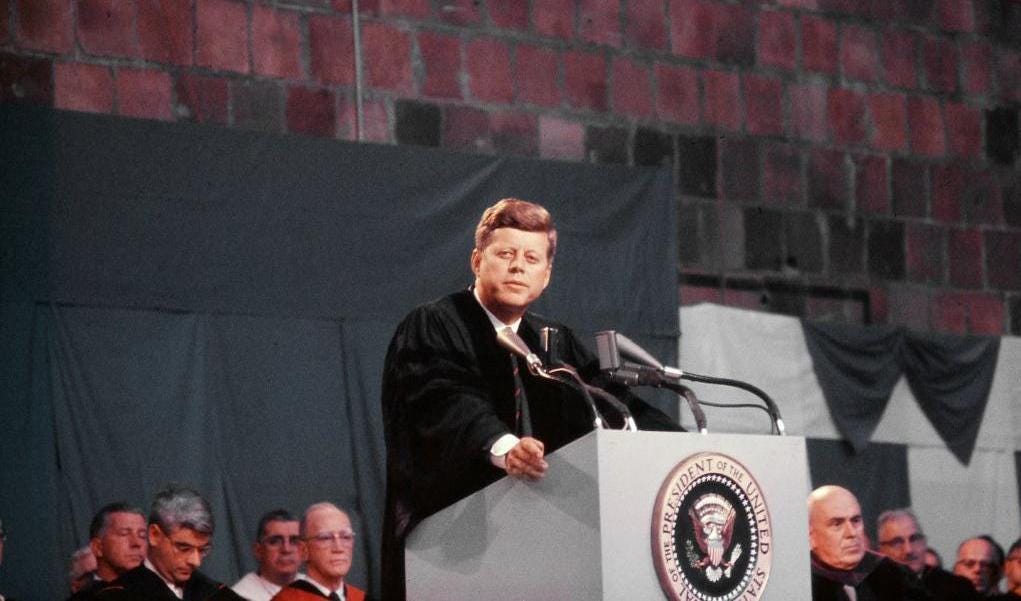

In 1989, the year I received my grant, Ronald Reagan was leaving office, replaced by George H. W. Bush. Conservative politicians like Jessie Helms from North Carolina had been attacking the NEA for grants given to artists they considered offensive. Over the years I followed these political attacks and began to research the history of the NEA. I learned that in 1963 President John F. Kennedy gave a speech at Amherst College shortly before he was assassinated. In that speech, he said:

I see little more importance to the future of our country...than full recognition of the place of the artist...Society must set the artist free to follow his vision where it takes him...And the nation which disdains the mission of art invites...the fate of having nothing to look backward to with pride and nothing to look forward to with hope.

President Kennedy believed not only in the importance of the arts but in the individual artists’ role in society. His vision, some say it was Jackie Kennedy’s, planted the seed for what would become, under President Johnson, the National Endowment for the Arts. The first Annual report of the NEA (which was initially called the National Council on the Arts) is a remarkable document. It lists the first board members which included composer Leonard Bernstein, journalist David Brinkley, fashion publisher Eleanor Lambert, writer Ralph Ellison, and architect Minoru Yamasaki, just to name a few. The report is filled with historical quotes from St. Augustine to George Washington, to President Kennedy, all emphasizing the need for the cultural development of art and individual artists.

For the next 25 years, the NEA would continue to grow and support new and established artists with direct, no-strings-attached grants. But the future of the NEA Artists Grants would not survive.

The Republican campaign to eliminate the NEA, which was coined the culture wars, not only attacked funding the NEA but also the character and artistic ideas of those who were deciding how the funds were being spent, and the artists themselves. Artists like Karen Finley and Robert Mapplethorpe were singled out as degenerate and their work obscene. The conservative right framed the source of contemporary art as decadent and corrupt, urban and elitist, while their preference for populist art was centered in the heartland and based on simple values and purity.

In 1997 then-Senate Majority Leader Dick Armey (R) of Texas would become the face of the aggression against the NEA. During a House subcommittee meeting, he testified that he had been personally offended by the very idea of the NEA ever since he took office and that the NEA should be defunded, claiming individual donations would do a better job of supporting the arts than the government. He stated that if needed he would teach the children art:

..because their learning of art from their grandmas and grandpas, and their neighbors and cousins, and their appreciation of learning to love that which is loved by the people they respect in the community, will sustain them far further in life than money and instruction from Washington.

See Armey’s full testimony here

The NEA no longer awards grants to visual artists. Shortly after Armey’s testimony, the NEA succumbed to the political pressure from the Right. The endowments appropriation was slashed and it stopped awarding grants to individual visual artists completely. Today what meager amount is yearly appropriated goes to art institutions and arts organizations on the state and local level, depriving artists of direct assistance.

Stay with me, it gets even weirder. The NEA doesn’t even use the word artist in its mission statement any longer. (see below to read the current statement)

As the snow continues to fall, I realize that this disturbing period of our cultural history is something that I often think about. Over the years I have questioned what is lost when art is attacked by a destructive political ideology. It is personal. I get angry that the program I benefited so much from, the program that offered me the time, space, and money to grow as an artist in society was destroyed by politicians and individuals who knew little to nothing about art, making decisions as if they did. I worry how far this disregard for artists has reached in our society. I worry that the word artist is being erased out for the word creative.

I fear what we have lost is the very seed Kennedy planted when he started the National Endowment for the Arts. We have lost the understanding, that art, poetry, music, theater, and dance provide us with the basic human truth which must serve as the touchstone of our judgment. Once that is lost, will we ever get it back?

Notes:

The current NEA Mission Statement:

The arts strengthen and promote the well-being and resilience of people and communities. By advancing equitable opportunities for arts participation and practice, the National Endowment for the Arts fosters and sustains an environment in which the arts benefit everyone in the United States.Rep. Armey (R) retired in 2003 receiving a yearly salary of $430,000 as chairman of Freedom Works, a conservative think tank that he chaired for over 10 years. After a disagreement on the future direction of the Freedom Works Armey accepts an $8 million dollar buyout.

It is unknown how much money, if any, Dick Armey ever donated to supporting the Arts in America, or if he ever taught art classes to children.

President Kennedy’s 1963 remarks at Amherst Collage

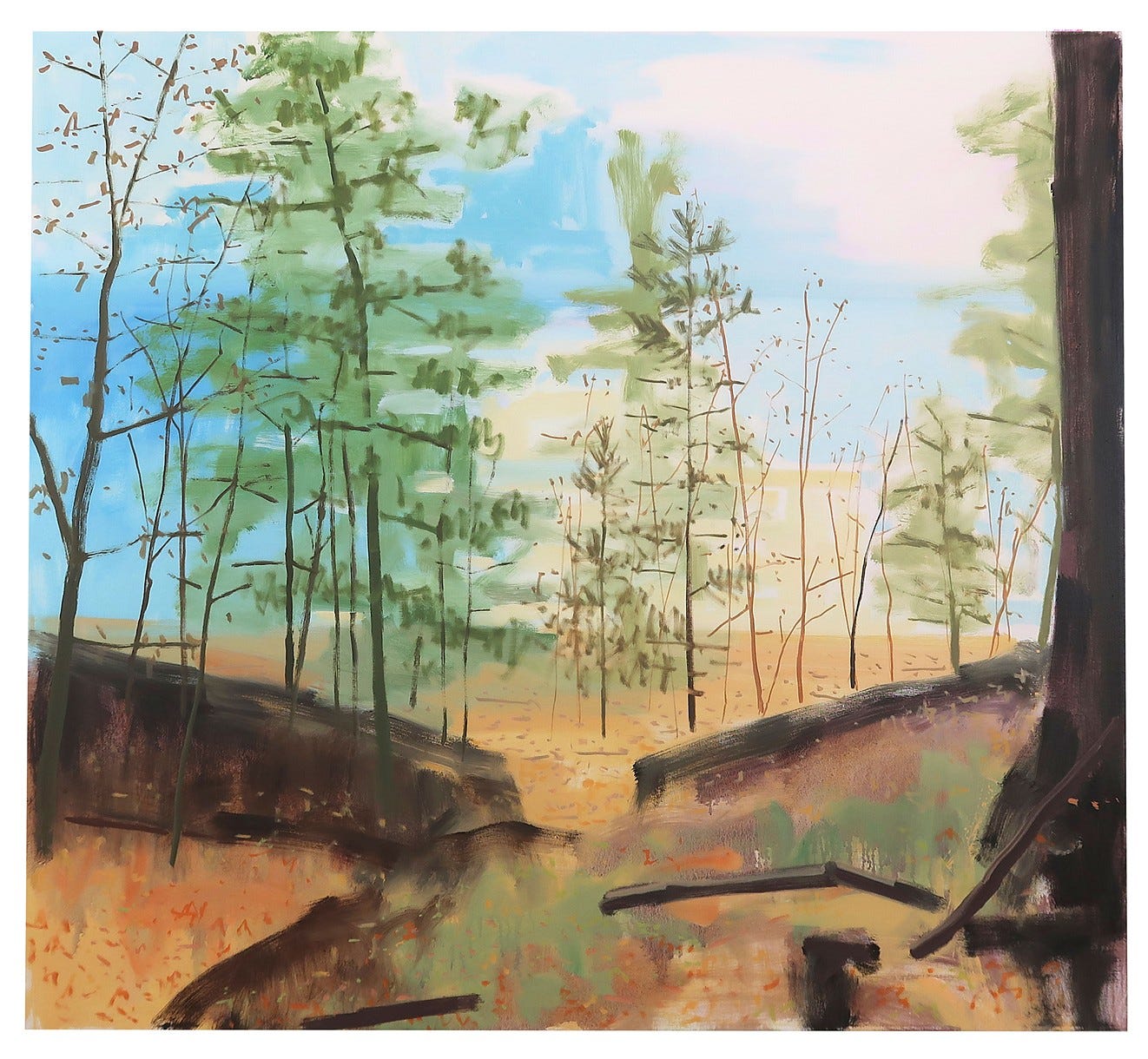

After all of that political angst here is a new painting of mine to help cleanse the palette.

Subscribing is free. And I promise not to flood your inbox.